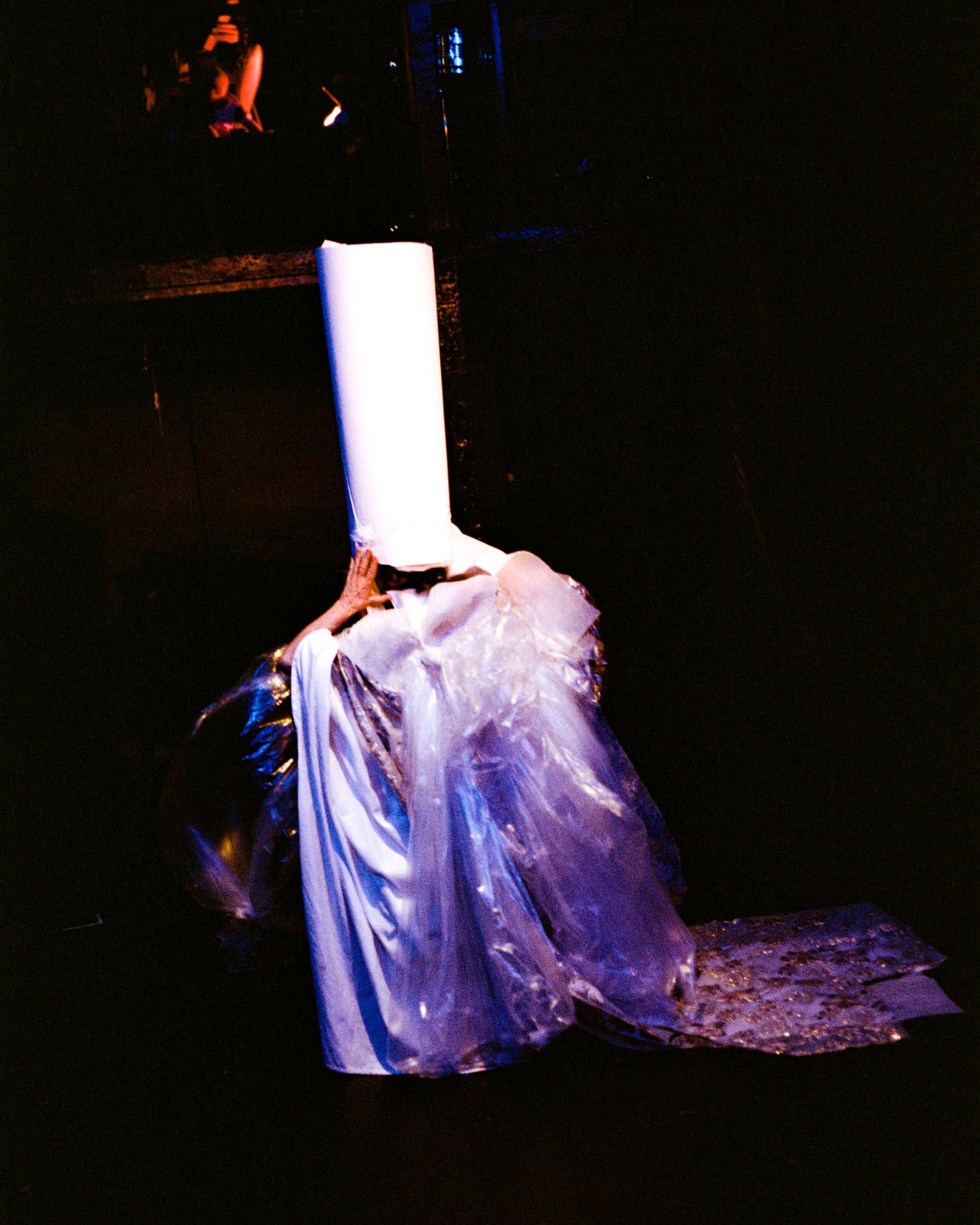

A breathless figure enrobed in transparent trash-bag balloons appears in low light, graceless-yet-angelic. With a tall pillar headpiece that veils writer and director Asher Hartman’s smiling face, the figure makes its way to center stage, gasping, groaning, and giggling—or maybe it’s a gurgling sob. They do a slow and belabored twirl and grasp the space in front of them, reaching to orient before finding a banister to guide them. Set designer Olivia Mole, sound designer Jasmine Orpilla, and assistant director Luna Izpisua Rodriguez—with her astoundingly quiet (real) baby in arm throughout the evening—are perched on a balcony at the top of the stairs, attending to the action below. Once the figure reaches them, Mole quickly disassembles the balloon suit and Hartman unfurls onto the balcony floor, winded and unadorned. A respite. But just as a hush falls, Michael Bonnabel pops onto the now fully-lit stage, an upside-down plague doctor mask strapped to his forehead and an oversized ribbon around his neck. The air molecules shift. If The Mommy Leaks the Floor is an ode to theater, Bonnabel’s entrance is a beat drop.

The Mommy Leaks the Floor

Asher Hartman at New Theater Hollywood

Review

All photos: Asher Hartman, The Mommy Leaks the Floor, 2025. Performed at New Theater Hollywood. Photo by Danielle Neu

In the frenzied hour of defiant pronouncements, tense interlocutions, and giddy non sequiturs that follow, I keep finding myself thumbing a question about generosity. Often used in post-show conversations to describe an actor’s performance, a director’s choices, or even an audience’s response, “generosity” gestures toward needs or expectations that can be exceeded, but doesn’t name them. Floating somewhere between offering and reception, it is both a statement of gratitude and an admission: “I needed that.” What needs can a performance meet? As my attention gallops to keep pace with the redirections of Hartman’s script, I am propelled by an overarching impression of generosity, fumbling to hold my own shadowy needs up to the light cast by this sense of surplus.

The play is not linear. The scenes do not lead into one another; they rub against each other and smother one another into submission. Bonnabel is joined by fellow frequent Hartman collaborators singer Philip Littell and curator José Luis Blondet. The words in their dialogue bend and prick. They don’t come out as they’re meant to and immediately offend. “What was that li[k]e for you?” “Lie? Why would I lie to you?” “I said Li-K-e.” “Is that a slur?” Inviting us to act on his own violent urge, Blondet asks the audience if we want to slay Littell with a mop (sword). In an anxious pause, we look at each other. Do we? Arne Gjelten, an audience plant, comes forward. A relief (generous). But Littell worries as Gjelten approaches the stage. “You’re not an actor, are you?” Of course, he is. “You’re not in this show are you?” He’s an actor and he’s here to act. “The stage can be slippery, by the way,” warns Bonnabel. This is a true statement. “It’s fake,” reassures Littell, as Gjelten shakily lifts the mop overhead. I’m not so sure.

Beyond the billowing black satin that skirts the theater walls—Mommy’s slip—Mole’s set design is not a body of materials but an instrumentalization of the body as scenic material. She strings together a charm bracelet of embodied interventions that offer the audience a subtle distortion. At one point she is leaning forward from the balcony to gently caress Littell’s head with her fingertips as he holds a stiff crucifixion pose. At another she slowly dribbles water onto the stage from her mouth. Another still, her limp arms and legs weave through the balcony banister like a rag doll, or a floppy growth. At this moment, Hartman’s body suddenly splats prone on the stage floor. Looking pityingly down at the splat, Littell declares the stage “a useless, faceless hag.” Poor Mommy.

Jasmine Orpilla is an aural alchemist, enlisting a junk drawer of sonic devices to expand the sparse black box theater into a wormhole. In some instances, the sound matches the action on stage, but at others the pairing feels associative, like a sensory slant rhyme. We hear the trigger of pre-recorded water rushing and synthetic crinkles underscoring the actors’ movements, the resonant live-sharpening of a knife followed by the violent chopping of vegetables as onstage tension mounts, the crash of a cymbal breaking a silence. In one ecstatic moment, there is an energetic transference as Orpilla takes over voicing the crescendo of a song Blondet had been singing, erupting into an operatic wail—a tidal wave that drenches us all. When Orpilla abruptly halts the sound, Gjelten collapses to the floor in uncontrollable laughter. The uncomplicated generosity a performance can offer: that Orpilla lets us feel the wail, that Gjelten lets us feel the laugh.

The actors continuously egg on, harass, and compete for attention. They speak fake French—with the exception of an identifiable mention of “poulet.” They cajole, titillate, and approach climax. And then, rather than following a trajectory, the bubble pops: “I was gonna say I love you, but I hate you.” The focus shifts, and what we had been watching disintegrates as a new scene comes into frame. In one moment, all three break into a jazzy chorus line insert, snare brush and all (sometimes generosity comes in the form of cheese). In another, a scene is interrupted when Gjelten suddenly receives an inexplicable, haunting phone call from Mr. Clean, the bald brand mascot: “Hello? Mr. Clean?! I just can’t be a relational object. I just can’t! [Fever pitch] I CAN’T!” It’s as if we’re zooming out to reveal another frame and another, but with no singular vantage to zoom out from, not getting closer to a central source. Instead, the frames burn up and melt away, making space for something else. The impact of this structural dynamic offers the opposite of cumulative meaning: a continuous shedding of attachments to the familiar scaffolding of meaning-making so that all of our senses can be untethered by the routinized work of understanding and left to surf associative waves.

There’s a piano on the stage. Faithful to convention—generosity: theater loves an audience plant and a fired gun—it eventually does get played. Thank you, Mommy. Littell unfolds a long and winding monologue in a crumbling descent through the audience aisle to the stage. Upon his arrival, Gjelten hovers over Littell: “Wow. That was great. But could you do it again?” Performance is a practice. At this point, each of the actors has notes. “First of all, I want to say: you’re amazing. You have really great energy! You’re really super, SUPER generous. I mean that.” There’s that word! Did I put that out THERE or did they put that in HERE? Littell concludes his gush of pleasantries with, “Maybe we don’t get along, but we’re gathered [at a time like this!], and that’s great.” Bonnabel chimes in that he “likes wine!” and would like to drink wine in the play—he hadn’t said it earlier because he had lines. Blondet adds that he thinks the audience should have been able to go to the bathroom during the show, even though it would have meant walking across stage in the middle of the play. GENEROUS. There’s a take down of superficial after-show flattery (because that is, of course, not generous). The others, Orpilla along with Hartman, Mole, Rodriguez, and baby watch over this wrap-up intently from the balcony while sharing a bag of chips, curious.

There’s a thrum of sincerity as the play decelerates toward an ending. Gjelten is still, his back relaxed against the wall, talking to us—or at least about us—offering an answer to what I’ve been groping around for. “You all have that, something hiding in your desire. Something waiting to be picked…” The space between us feels gossamer-thin. “But isn’t there something less obvious? Something stranger? Something less utterable. Something more ineffable. Something that can never be… said.”